Since moving to Ireland in late 2003, Dr Umar Al-Qadri has become a prominent figure in representing the Islamic voice in Ireland. Having received a traditional Islamic education in Pakistan, Al-Qadri went on to obtain a master’s degree in Islamic Sciences. Making frequent appearances in Irish publications like the Irish Times, he also lectures across the country in mosques, community centres and universities about Islam and the the challenges that Muslims face today.For Al-Qadri, the integration of the Muslim community into wider Irish society is something of a priority. In Ireland, there are now an estimated 70,000 members of the Muslim community, and at home and abroad, Muslims are increasingly facing marginalisation, persecution and criticism. As the spotlight is placed on Muslims the world over, I sit down with Al-Qadri, the Head-Imam of Al-Mustafa Islamic Educational and Cultural Centre Ireland, in Trinity’s Science Gallery café to discuss our Muslim community here and the challenges they face.Our Muslim community is not immune to the sensationalised and inaccurate representation the religion sometimes receives in the media across the world. Neither too do they avoid the fate of being too often rendered largely invisible within Irish society. Al-Qadri’s response to this is to stress the idea of people all living as one. He stands for equality and mutual respect between groups as something essential for modern nations, an ideology that informs many of his own actions.Our interview begins with Al-Qadri tracing the origins of Ireland’s Islamic history to one man, Mir Aulad Ali Khan, one of Dublin’s first Muslims, as well as a scholar and professor of religious studies in Trinity in the 1860s. Al-Qadri describes him as very well integrated, and who at the same time maintained his own identity and wore his traditional Muslim clothing. It was only in the 1950s, however, that Muslim students began to come from South Africa to Ireland to study medicine. It was these students who formed the first Muslim community to establish themselves here. This tradition, continuing throughout the 1990s, allowed for a well-educated Muslim population to develop in Ireland. Since then, the numbers have grown from 33,000 in 2003 to upwards of 70,000 now, Al-Qadri tells me. The community has changed too. While it was previously based around the medical and scholarly professions, it now represents a diverse group of people from many walks of life, ranging from taxi drivers to IT professionals. Often, he adds, you cannot tell a Muslim apart from any other Irish person. They often do not have dark skin, while many choose not to wear traditional Muslim dress, he explains, gesturing down towards his sharply tailored suit. He humorously adds that perhaps only the beard would give it away.

Muslims, when they have friends that are consuming alcohol … they will interact together, but they won’t drink themselves and they will not treat the person that drinks alcohol differently. But they will treat someone who is gay differently, and that is something that is not understandable.

Al-Qadri’s early years were spent in the Netherlands, where the he remained until he’d completed secondary school. He highlights this time as a formative period in his own ideological development: “I wouldn’t be the same person I am if I didn’t grow up in the Netherlands … I think my ideas have been shaped by my experience growing up in the Netherlands as a second generation Muslim.” It was there he witnessed first-hand the challenges that many Muslims face across Europe. The years he spent here were during a period of Dutch history characterised by the dominance of right-wing conservatives, who were in finally in government after years of steadily increasing their vote in elections. The party, which he describes as “anti-Muslim and anti-Islam”, pushed Muslims to live in isolation and caused them to be segregated from the greater population. The reason that Al-Qadri believes that these problems arose is because the “Muslim communities that lived in the Netherlands somehow failed to reach out to the other and failed to integrate”. By this he means integration beyond purely language and dress, with the community perhaps not doing enough to counter those who sought to marginalise them.

Motivated by the desire to do something for his religion, Al-Qadri wanted to avoid making the same mistakes in the newly-diverse Ireland’s young Muslim community. In an earlier stage of development and with an educated and professional Muslim population, he perhaps thought he could help Irish Muslims and write a different narrative for the minority group. The way in which to achieve this, he believes, is by reaching out. This, after all, is the teaching of the Prophet Mohammed, he tells me, who “welcomed communities and opened the doors of the Mosque to others”. This is something that Al-Qadri firmly holds to be true.

He believes that Muslims often isolate themselves in an effort to protect their faith and identity, something that is, in fact, damaging for the community. “We are living in a society where people do accept and tolerate other views. We should reach out and not be afraid”, he urges his fellow Muslims. His recent invitation to members of the LGBT community to the mosque’s end of Ramadan meal in June reflected this sentiment of inclusion. “As Muslims we must reach out to others’’, he says, “we must not treat people differently because of their lifestyle or beliefs”. Although such an expression of kindness and support appears radical in relation to the more stereotypical image the religion being strongly doctrinal, Al-Qadri cites the teachings of Islam as the foundation for his argument, where you must treat people as human beings first – something which he says has been lost among many Muslims.

Nonetheless his actions were still somewhat radical, and he came under criticism from the group that he represents for reaching out in this way. Some felt that this gesture was akin to him condoning homosexuality, but in the face of the controversy, he stands by his actions. “Inviting them does not mean that we condone or that we agree with [homosexuality]”, he explains. “It means that despite our disagreement we can still share a meal together”. Although he does not condone the act, he believes that the LGBT community, like Muslims, share similarities. The two minority groups have both been marginalised and should join together against a common injustice. He gives a practical example to support his decision to invite LGBT members to the event, which he hopes that Muslims will be able to appreciate, drawing a comparison between the two Islamic sins of drinking alcohol and homosexuality: “Muslims, when they have friends that are consuming alcohol, they would be okay with it, they will sit down together, they will interact together, but they won’t drink themselves and they will not treat the person that drinks alcohol differently. But they will treat someone who is gay differently, and that is something that is not understandable”. Al-Qadri emphasises that the teachings of Islam are to treat people as humans first, and the success of the meal, which had over over 20 LGBT members alongside some Muslims all enjoying themselves together, stands as testament to that.

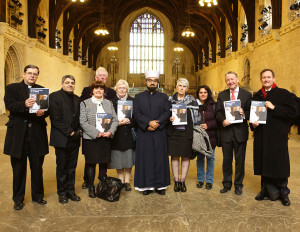

“Seen here with Leo Varadkar, Dr Al-Qadri has come under criticism from his group for reaching out to the LGBT community. ”

Credit: Umar Al-Qadri photo

After the Charlie Hebdo attacks of Paris 2015, which many would see as a watershed moment in the story of Western Muslims, Al-Qadri founded the Irish Muslim Peace and Integration Council. He points to the need for a council that promotes peace and integration in Ireland, which is also capable of leading the community towards this aim at the same time. At a time when the West is falling victim to attacks of the extremist group ISIS, who operate under the name of Islam, Al-Qadri insists that it is Muslims who are often the victims as much, if not more so, of effects of extremism. The religion, he says, must often carry the burden of blame in the aftermath and is often the focus of damaging generalisations from the public. He recounts a scenario that for many Muslims is a daily occurrence: “As Muslims you sit on the bus, and if you look like a Muslim, people really will show you their discomfort. If you are wearing a Hijab, you’ll be abused on a daily level, that is what is happening with Muslim women.” Al-Qadri is actively trying to subvert the connection with any extremist branches of the religion, holding a “Not in Our Name” protest in Dublin city last summer in an effort to separate themselves from segments of Islam that do not accurately reflect them and to show that these extremists have nothing to do with Muslims who go about practicing their faith in daily life. For Muslims living here, he asserts: “Our needs are the same as any other Irish person, you know, we have families that we are raising, we have challenges that everybody else is going through in life, the issue of housing is one.”

Sitting relaxed but upright at the far end of the Science Gallery café, he answers my questions in a calm and considered manner, each word seemingly carefully chosen. Emphasising the role and responsibility of the media in the misrepresentation of Muslims to the wider audience, Al-Qadri is visibly passionate about the issues that they face. The media, in his eyes, is guilty of perpetuating and further producing Islamophobia through the mass generalisation of a large and diverse group of people, arguing that “the news is very sensational, so a lot of Muslims, they become victim of Islamophobia because people generalise, ok this is a Muslim, every Muslim must be like that”. An unequal telling of atrocities, as he sees it, tends to focus on those of Muslims rather than any other religious group. This doesn’t represent the community as a whole, but only a particular branch of it, building walls while also unintentionally creating extremism, he says.

This bias in the media, he says, is everywhere, sensationalising stories and reporting on events which neatly fit into their narrative of Islamic terrorism. He feels that the same attention is not given to Christian atrocities: “When the same [atrocities] have taken place by a Christian, you never hear the religion because the religion doesn’t make a difference.” The narrative of the media in their reporting of stories should be “balanced and have to have one standard” the Shaykh thinks. Muslims, in response, feel that they are not being accepted into society and feel they are being targeted deliberately in this way. Al-Qadri does, however, clarify by saying that he has not found this to be true of the Irish media, an institution which often seeks to understand rather than to cast blame, saying that “the Irish media compared with the media in Britain or Holland, it’s not anti-Muslim, you really get the sense in Britain and in Holland that the media is biased, but here it isn’t”. This is something he very much appreciates. The media, whether print or digital, is a significant platform upon which to amplify the voices of groups and getting across what they believe. It is clear that Al-Qadri sees the value in engaging with it (or he wouldn’t be speaking to me) and recognising it as an important tool to extend his message beyond the Irish Muslim community and towards the larger public.

In Islam, the Head-Imam insists, women do not wear the hijab because it is imposed onto them. When I ask why might a woman chose to wear the hijab, he respectfully tells me that I would have to ask a woman.

Al-Qadri believes in the integration of communities, rather than assimilation, celebrating differences yet living as one. In Ireland, while many young people turn away from the organised religion that was imposed on them, young Muslims are experiencing the opposite, with increasing numbers turning to their faith. When living in a country as a minority their religion is something that they understand and where they can find support. It is a religion that, according to Al-Qadri, gives you the choice, rather than imposing its teachings on you. In Islam, the Head-Imam insists, women do not wear the hijab because it is imposed onto them. When I ask why might a woman chose to wear the hijab, he respectfully tells me that I would have to ask a woman. He does concede, however, that his understanding is that many would wear the scarf to protect their modesty, just as God tells them to, as well as a symbol of their Muslim identity – a sense which only grows stronger in the face of marginalisation. The hijab, contrary to popular belief, does not mean headscarf but is a concept in Islam for both men and women. In fact, in the Quran the hijab of the man is more important than that of the woman. It is to lower their gaze and to look without lust. Men must also cover from the belly to the knee.

In an attempt not to cause offence, I avoid the term “burkini” and ask him what his opinions were on the “burka swimsuits”. Al-Qadri tells me that he does not take issue with terminologies and embraces the term “burkini”. He believes that France’s approach is wrong in banning the swimsuit, declaring that “this approach of the French government will only increase extremism”. Recently tweeting an image of a nun on the beach, Al-Qadri summed up the hypocrisy of the ban. The rules that apply for the expression of Christian faith, from a Muslim perspective, is a freedom that is not extended to them. Just as the marginalisation of Muslims only causes greater dedication to their faith, so too does banning of the modest swimwear to them. Al-Qadri thinks that this act “will only increase distances between communities”, he says, mulling over the remnants of his black coffee. Responding in this way, he says, gives the impression to Muslims living in the West that they are unwelcome. Instead, there is a need to educate people, saying that “the government should have actually created awareness and help people to understand why Muslim women choose to wear the burkini”.

As we conclude the interview, Al-Qadri tells me about the charity and generosity he sees from the Irish people, a people that extend integrity and respect to all of its diverse members and are accepting of others. Despite this Ireland’s promise, which was made during the Celtic Tiger to immigrants living here, to provide additional resources which would allow them to integrate more efficiently, has, since the recession, been placed on hold – the provision of English language classes for example.

Al-Qadri’s message of acceptance and integration was clear and without exception, even in his approach to our LGBT community. Through the work of community leaders like him, people are starting to think about how the Muslim community in Ireland are treated, and how to support their integration into the country. From talking to Al-Qadri, it is clear that he would hope that next time you see a woman wearing her hijab, you would treat them as both a Muslim who is secure in their identity, and more importantly, as an Irish person going about their day.

Source: http://www.universitytimes.ie/2016/10/in-a-dublin-mosque-a-very-modern-sheikh/